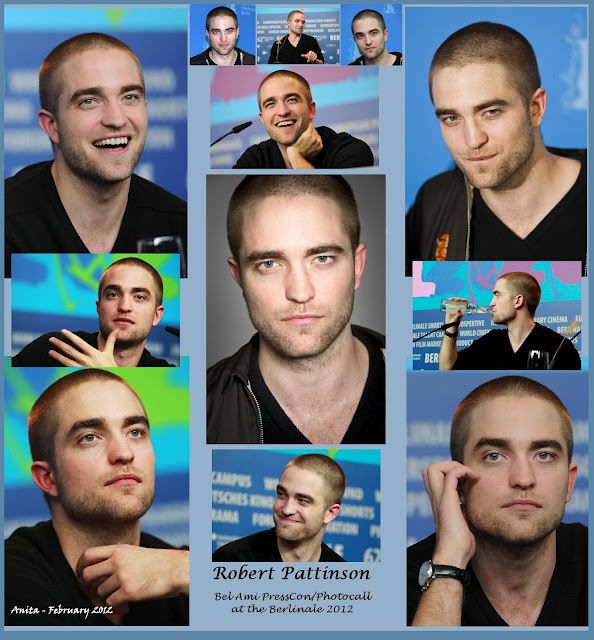

"The world’s favourite vampire is in Berlin for a whirlwind visit and,

true to bloodsucking type, Robert Pattinson isn’t eating. Tonight, he

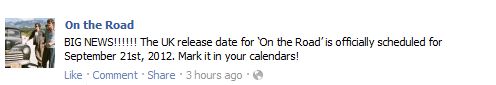

will do the red-carpet thing for the world premiere of his new film, Bel

Ami, but in the private hotel lounge allocated for this interview —

“This is classy,” he comments as he strolls in — he barely makes a dent

in the chicken salad he has ordered, despite his professed hunger.

Pattinson

isn’t known for playing characters who do much smiling or laughing,

either, so the first thing to notice is how readily he does both in

person. Decked out in a black-grey ensemble and sporting a new cropped

haircut under his black cap, he has barely sat down, with a pack of

Camels by his side, before he’s folded up in mirth, talking about the

KitKatClub, a notorious Berlin sex joint, and his desire to patronise

it with his family. Is he joking? I hope not. “I was telling my dad

about it last night, and he sounded really into it. ‘I’m coming over —

let’s go to the orgy club.’ ”

The 25-year-old actor has been

to Berlin many times. One of the best holidays he ever had was a stay in

the east when he was 17, “before it was so gentrified”, frequenting

bars that took up illegal residence in abandoned buildings. Such

footloose times are seemingly in the past for the star of Twilight,

although his desire to hit the KitKatClub may indicate otherwise. The

other observation to make is that Pattinson is a very handsome man, but

his face is less wide and flat than the camera makes it appear. And

there are enough imperfections to separate him from the standard

Hollywood pretty boy.

Nobody wants to see a dickhead succeed — that’s why I wanted to do it

It

is easy to see why he is ideal casting as a heart-throb vampire, but

equally why he got the role of Georges Duroy, the insatiable

money-and-lust monster at the heart of Bel Ami. This adaptation of Guy

de Maupassant’s belle époque novel marks the directing debut of two of

our most acclaimed theatre practitioners — Declan Donnellan and Nick

Ormerod, the founders of Cheek by Jowl. Of the projects Pattinson has

chosen with the Twilight safety net in place, the first two, Remember Me

(2010) and Water for Elephants (2011), were unadventurous romantic

excursions, unlikely to perturb even the most rabid Twihard. Bel Ami is

where it gets interesting.

Georges Duroy is essentially the

anti-Edward Cullen, an opportunistic cad who deploys sex for ruthless

gain, screwing people — literally, in the case of the rich society wives

played by Uma Thurman, Christina Ricci and Kristin Scott Thomas — on

his rise from impoverished soldier to powerful Parisian. Cullen is the

charming, soulful vampire who gets the girl; Duroy is the charming,

soulless parasite who gets everything but his own comeuppance. Pattinson

nails his repellent, empty charm, sneering as he seduces.

Sticking

closely to the Maupassant source is one of the many strengths of

Donnellan and Ormerod’s gorgeously realised vision, and Pattinson

admits that tweaking Twilight-fuelled preconceptions was an original

lure. “But my ideas about it changed as I was doing it,” he says.

“Georges keeps getting beaten down by the world, but he never learns. He

succeeds because of the bad points of his personality. Nobody wants to

see a dickhead succeed — that’s why I wanted to do it.”

For their

part, Donnellan and Ormerod are predictably effusive about their star:

the former praises his “passionate attachment to us” during the film’s

difficult financing, and credits him with “edge and intelligence”.

“There’s a huge difference between Georges and Rob,” Donnellan says.

“Georges rises to the top with no talent. Rob has masses of it.”

(Donnellan sees Bel Ami as a parable on modern celebrity culture.) They

also attribute the idea for a five-week theatre-style rehearsal process

to the actor, a savvy move that allowed him to soak up their reservoir

of knowledge about performance and period. He showed up every day for 10

or 11 hours. “I ended up doing mime and crazy improvisations, because

you run out of stuff to do,” he says. “One day, Holliday [Grainger, his

co-star] and I ran around screaming at each other for four hours.”

Pattinson can’t articulate how the process fed into his performance,

although when he arrived on set in Budapest in February 2010, he was

worried he had overcooked it.

Meanwhile, Ormerod and Donnellan

were taking the baby steps that come with being debut film-makers. The

former focused on the design tapestry, the latter on the actors.

Pattinson recalls them putting a row of audience heads at the bottom of

the monitor, but the graceful storytelling they bring to Bel Ami bodes

well for their move from stage to cinema. “We’re now rather bitten, I’m

afraid,” Donnellan says.

Published in 1885, Maupassant’s

masterpiece was shocking in its day. The author knew he was on borrowed

time while writing this, his second novel — he eventually succumbed to

syphilis — and it is infected by a spirit of nihilistic hedonism, of

indulging base instincts while you can because, as the antireligious

Duroy puts it: “This is the only life; there’s nothing after.” Pattinson

wishes they had kept a shot near the end where Georges turns to a

crucifix and thanks God for his good fortune. “It was done in the most

blasphemous way,” he says, “thinking of God as Father Christmas, which

was funny. There’s a lot of misery in the movie. It’s not as funny as I

thought it was going to be.”

Read MORE after the cut!